Red, white, blue’s in the sky. Summer’s in the air, and baby heaven’s in your eyes.

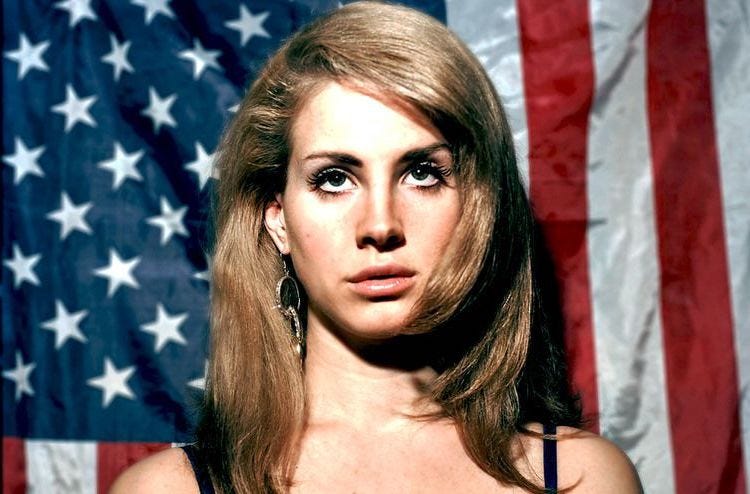

The most American I’ve ever felt was one Fourth of July after my freshman year of college. The memory is preserved only by a video I recorded of myself on Snapchat: in it, I’m sitting by the pool of a sprawling country club home that belonged to my boyfriend’s mother, raising up a frozen margarita in a plastic coupe. I’m wearing a black push-up bikini top, with my sunglasses propped just-so to push back my hair into a messy approximation of 1960s bouffant. Lana Del Rey’s “National Anthem” is blasting in the background. I’ve covered part of my face with the text: frat trophy wife vibes.

Later that evening, I would regroup with my suitemates to pass around a fifth of Fireball before frisking off to the school’s football stadium, to watch fireworks crack and whistle in the static southern air. Nothing really happened then, except that I felt at once the satisfaction yes, this is it, this is what I’m meant to be doing, and a vague feeling of reproach for the whole scene. The text said it all: a cheeky declaration that I knew what I was leaning into. Suburban poolside child-bride.

=

Born To Die, Lana Del Rey’s 2012 sophomore record, has about as much content about alcohol, drugs, partying, sex, and love-at-first-sight as anyone could expect from a pop album marketed towards teenagers of that era. But there was something remarkably different about Lana’s world: she exchanged the scenery of modern-day clubs for poolsides, winding roads, hotel rooms, casinos, and other trappings of 1950s and 1960s America. Born To Die was like a meticulously-detailed period piece, yet it still somehow held purchase in our real-time sentiments, perhaps charged only with the urgency of our raging hormones. Each track was a catchy summer anthem with an orchestral undertone of doom. In terms of the lyrical content, there were always women who kept up a drooling, steadfast devotion to their lovers with questionable morals (gangstas, sinners), sometimes in the name of an attractive type of wealth: Money is the reason we exist / Everybody knows it, it's a fact / Kiss, kiss. Among this aesthetic of desperation existed a sense of reckless abandon and the promise of a James-Dean brand of death: excessifyin’ / overdosin’ / dyin.’ There was the type of submissive trophy wife who, in spite of ascending to the heights of love, is relentlessly miserable—the same character who would manifest in her later albums, the one who would echo the classic and controversial refrain: he hit me and it felt like a kiss.

Lana laid down her motifs carefully, winding them tightly between a dichotomy of sweetness and danger. Even the wild, liberated tones of the sleeper hit “Summertime Sadness” came with atmospheric dread: telephone wires sizzling like a snare to signal the looming threat of self-annihilation. Most importantly, perhaps, was that Born To Die felt quintessentially Young and American. Blue jeans, small-town firelight, Pabst Blue Ribbon on iceeee! And on the cover of this album was the image that would launch one thousand obsessions in Tumblr-teens: a red-lipped strawberry blonde standing in front of a suburban pool fence, gazing placidly at the camera, filtered through the haze of summer light.

I first encountered Lana Del Rey when I was learning how to feel. I’d listen to Born to Die late at night after having drank a glass or two of my father’s wine in my bedroom, or in earbuds while slumped in the passenger seat of my mother’s car as she drove me to and from weekly therapy sessions in the next town over. I, too, felt inexplicably alone on a Friday night, I imagined myself too trying hard not to get into trouble, yet having a war in my mind. It was easy to categorize my sixteen-year-old angst this way, stretched thinly between maniacal bliss and utter despondence. Yet I think I was aware, on some level, that my life was easy enough: Lana’s dysfunctional version of old Hollywood glamor had very little to do with me. Born To Die was an escapist fantasy, a costume that felt good to slip on intermittently.

=

I’d just started college at a giant public university in the same town I’d grown up in when I decided to take a stab at fitting in. I was seventeen when I began mimicking the ensemble of gym shorts and sweatshirts I’d loathed only a year prior, and swapping tiny “going out tops” among my suitemates to pair with light-wash jeans and white trainers on the weekends. We’d mix vodka from a plastic handle with anything we could find from the first-floor vending machines, take videos of one another attempting to twerk to Waka Flocka Flame, and then take the campus bus north to where neat rows of fraternities awaited us.

These suitemates soon taught me that the neon paper bands that would allow access to these parties were a type of currency. They could buy you any number of fine freshman goods—popularity, a good night-out story, or, if you were lucky, an invite to a cocktail or formal—all without the hassle of actually rushing a sorority.

This was a game I tried to take seriously: I found myself dancing with a sweaty man in a Hawaiian shirt one evening, and although I’d initially thought he was gay, he tracked me down on Instagram the next morning and told me he’d found my name on the list. I soon began to procure invites to themed parties: fifth-and-a-cuff, Edward-forty-hands, et cetera. My friends were proud of me, and I told myself that AEPi was one of the better fraternities. It was low-ranking and didn’t have a reputation for any particularly attractive or wealthy men, but they had security cameras in the house and their sexual assault statistics remained on the lower end. I told myself they were nice guys. My date was ditzy and devoted: he loved his father, loved football, loved PBR, loved slightly sadistic sex. I believe our relationship began once he began referring to me as his girlfriend. I recognized that I had no feelings toward him whatsoever, but it seemed pointless to resist. It felt like I had won the jackpot.

By the end of spring semester, my suitemates were tagging along to some of the biggest “darties” on north campus, clad in derby-esque sundresses we’d bought from Target or Forever 21. But it was only I who was proper royalty, with my “cuffed” status, allowed full access to the house day and night. I dutifully drove my boyfriend to and from Beer Pong League matches, and the brothers began to know me by my name. On Sunday mornings after parties, I swept my hair into a high ponytail in the hall bathroom covered in tiny dark hairs I could only hope were beard trimmings. I’d walk downstairs and pad around through the empty house, my sneakers making sticky noises against the depressed wooden floor. It all felt very foreign, yet very familiar—this brand of University Americana I’d only seen from a distance, and now found myself lodged in the very heart of. I belonged, and I had achieved some degree of success in the eyes of others. Frat wife. Not quite a sorority girl, a distinction I clung to: beneath the charade, I was troubled, and different, and somehow deep. I wasn’t really like this and nobody understood—how very Lana Del Rey.

But by the time I made it over to my boyfriend’s mother’s house the following summer, I was already hatching a plan to break up with him. I knew that he hated me, on some level, for every time my facade wavered and I had something moderately interesting to say. I was bad at hiding my disgust for his generational wealth, and my resistance to his idea of a heterosexual relationship complete with old-fashioned power differentials. But it’s not like I didn’t try. I tried to uncover some value in being a trial version of trophy wife by listening to Lana on loop, of course.

It was Lana who turned that poolside into a worthwhile idyll. She seemed to understand the point of being with someone simply because they were moneyed and set on the road to greater success, to admire them for their social standing, to cling to their side with drunken, doe-eyed acquiescence—that classic American way. I, too, deserved my reward for our transaction.

He says to be cool, but I don't know how yet / Wind in my hair, hand on the back of my neck / I said, "Can we party later on?" He said, "Yes"

=

Yes, Lana understood, but it was unclear whether or not she truly bought into that way of life. It was hard for me to process then how much she really condoned the relationship dynamics she sang about—was Born To Die her gospel?

I could have sworn I’d heard it in her voice: something like clever mockery. Her vocals seemed to have as much disparity as her quickly oscillating lyric moods. In Born To Die, girlish shrieking that bordered on creepy would suddenly drop to a low, syrupy rasp, as if she was conspiring with the listener. By 2020, she’d already generated so many stock personas and tropes for women that her discography seemed positively literary, layered enough to distance the not-so-savory characters far from their author. After all, her albums were chock full of references to American letters, incorporating nods and quotes from Tennessee Williams, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Charles Bukowski, Henry Miller, and Hunter S. Thompson, to name a few—she even had Nabokov’s name stamped next to Walt Whitman’s on her inner wrist. I assumed that Lana had done her reading. And I respected her ability to embody multitudes through her own writing, because I believed that this was the control that came with any brand of art-making. There was something empowering in the way she hyperbolized these passive, vulnerable, desperate, evil characters to the point awful, laughable clarity.

Yet several years and several albums later, she would post a typewritten letter to her Instagram, titled “question for the culture,” which contained the following:

I'm fed up with female writers and alt singers saying that I glamorize abuse when in reality I'm just a glamorous person singing about the realities of what we are all now seeing are very prevalent emotionally abusive relationships all around the world.

I remember wanting to read the note as satire. Had I simply imagined that sad little smirk of hers? I’d given her the benefit of the doubt, trusted her critical eye—perhaps it was this impression of her music that made me feel as if I could easily shed the frat wife costume for something else, when the time came. I didn’t want to be doomed, I wanted to remain above it all. I wanted to laugh painfully with Lana, not at her. At least not at myself.

And I wanted to argue that there was a difference between ironic exposure and actual glamorization of the dark side of the American dream, but I couldn’t defend Lana’s graceless choice of words. Perhaps she had betrayed us all. I tried my best to avoid forming a parasocial relationship with a person who was really named Elizabeth Grant, who had been born in Manhattan, not in the suburbs of the American South. It was difficult enough to relate to someone so famous that they might be so out-of-touch with reality, or to pretend I could understand her real life in relation to her “artistic process.”

And whenever I heard “National Anthem,” I would still inevitably relive that time by the pool in a state of amusement, as if I’d once acted a minor role in a commercial for a product I didn’t want to buy. I’d ended up breaking up with the frat boy, and later had to file a campus-sanctioned restraining order against him. I realize now that I had been cruel—I had misled him, had used him as a prop in my experiment, because I had no idea who I was. Maybe remembering this time is another component Lana’s escapist fantasy, even if it had repercussions in my real life, even if it was lived in the moment as a fantasy, too. Maybe there is ignorance in this, a certain privilege in “just trying out” an approximation of other peoples’ suffering: emotionally abusive relationships all around the world. I was lucky to get the chance to start over later that summer, alone in the silence of the deserted campus’s library stacks, having abandoned the frat wife costume forever.

=

I reencountered Lana Del Rey over a decade after the release of Born to Die. I was a real adult under the influence of drugs, and I sat on the couch of an old college friend in an unfamiliar city and watched the music video for the song “Ride.”

The video opens with a shot of a young Lana suspended on a tire swing in an empty desert. A voiceover begins before the song does, a whispery, coquettish monologue: I was always an unusual girl, my mother told me I had a chameleon soul. No moral compass pointing due north, no fixed personality. Just an inner indecisiveness that was as wide and as wavering as the ocean. And if I said I didn’t plan for it to turn out this way I’d be lying – because I was born to be the other woman. The rest of the video flashes through shots of Lana in different scenes, wearing different costumes, flanked by different men. She’s in a Budweiser tee, closing her eyes and raising both hands on the back of a motorcycle on an open desert highway. She’s in a short white dress, sitting on a man’s lap on the balcony of a run-down apartment complex while he drinks a beer. She’s loitering outside of a convenience store late at night, sipping an orange Fanta in denim cutoffs. Again she sits in someone’s lap, in a denim jumpsuit and a big red bow while a man brushes her hair. She’s sharing a cigarette before getting railed against a pinball machine. She’s all done-up and singing on a stage. She tosses her brunette ringlets in slow motion and wraps herself in an American flag. Finally, she’s back in the desert at a bonfire full of those rambunctious motorcycle men, waving a pistol and wearing an enormous feathered headdress, while stray fireworks twirl through the smoke. As she mouths lyrics, her face shifts from a picture of pain to absolute delight.

It’s one of the most melodramatic, excessive, culturally-questionable pieces of Youtube cinema I’ve ever seen in my life. If I had been sober I probably would have laughed: she can’t be real with this. But instead, I cried. I placed my face inches from the television screen. Chills ran through my entire body. I fell under the delusion that she was God.

Yet it probably wouldn’t have taken chemically-induced psychosis for me to appreciate the full spectrum of gritty, fucked-up Americana fantasy Lana captured in “Ride.” It was what I had always loved about her work, even if her image has been re-appropriated in the same way that Nabokov’s Lolita had been in today’s Internet cultural consciousness. Later, I saw a Tweet that read:

i’ll never understand how lizzy grant became the it girl of the coquette aesthetic. she was a classic rock, motorcycle gang, david lee roth, alabama, trailer park, heavy metal, americana, nirvana girlie with weird unsettling vibes and that's how she should be remembered !!

I recognized some truth in this, but in reality Lana Del Rey had at least briefly embodied all of these things, and more. Perhaps this meant she was never once the it girl of anything in particular. They were all parts to play, as precise as they were contradictory, all of them somewhat weird and unsettling. Who knew how true any of these personas were to Lizzy Grant? She was simply a pop star with a sultry voice and a knack for poetic language.

In “Without You,” a track buried deep in the deluxe version of Born To Die, Lana echoes the ick-inducing note she would produce years later: Everything I want, I have / Money, notoriety, and rivieras / I even think I found God / In the flashbulbs of the pretty cameras / Am I glamorous? Tell me, am I glamorous?

It’s difficult to tell how authentic or plain-faced she wanted to come across in these lyrics. Yet at thirty-seven years old, worth $30 million, with nine and counting studio albums already behind her, Lizzy Grant seems to have shed nearly all of her concern for traditional glamor. I feel strangely touched whenever I stumble across a paparazzi snapshot of her at a gas station, now many pounds heavier, in raggedy outfits that look like they were purchased at K-Mart, striking convincing poses of the White Trash Americana she’d romanticized in the “Ride” music video.

I think again of that monologue: No moral compass pointing due north, no fixed personality. Just an inner indecisiveness that was as wide and as wavering as the ocean. Lana Del Rey’s claim on the chameleon soul seems fitting, now. Her discography and her image as a celebrity—in spite of their many limitations—contain multitudes of conflicting moods, sounds, personalities, and places. Now it seems as if teenagers glom onto online niches of “aesthetic” as a way to try to understand themselves, just as I once did. Now I recognize this type of identification as more mutable, even fluid, and never too serious.

After I encountered Born To Die as a frat wife, I think I wanted to believe that I would never be pigeonholed to just one iteration of Young American Woman. I wanted to live a life that was just as dynamic and two-fold as Lana’s arrangements. And even more so, I wanted the control of acknowledging that I’d somehow planned for it to turn out this way. The inevitable death that comes with birth, and vice-versa, the infinite times I could reinvent the image of myself. As if frat wife was simply another track I was dancing to, singing along to, and waiting for to end. ==